Billy stood on the ridge and looked north to where the dome of St Paul’s rose over the city, surrounded by a forest of chimneys disgorging a steady stream of pale smoke into the darkening sky. The chimneys were calling to him. It was time to go back.

Plunged into the criminal underworld of Victorian London, Billy the chimney sweep knows he must fight – or die. But with notorious gang leader Archie Miller closing in on him, every turn he takes only leads to more trouble.

When the ‘Poor Man’s Earl’ offers Billy a chance to exchange his gangland life for an education, Billy must decide if his pride is too high a price to pay, and whether turning on Archie will mean freedom – or certain death.

A thrilling story of faith and survival, based on the work of the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury.

Published by Wakeman Trust, 2020

R.R.P. £7.99

ISBN 978-1-9131-3310-8

Praise for the author

“Billy’s story was achingly real and the drama was so tense in both the chimney climbing scenes and the ones where his choices lead him deeper into danger and despair.”

Susan Brownrigg, author of ‘Kintana and the Captain’s Curse’ and the Gracie Fairshaw Mysteries

“I really enjoyed this account of Victorian London. The history is well researched but doesn’t get in the way of a good yarn here. Lord Shaftesbury is portrayed here, yes, but he does not take centre stage. That spotlight is reserved for the ordinary people, and the book is all the better for it. I read this while on a visit to London and as I looked around me, the centuries simply fell away. Excellent.”

Barbara Henderson, two time Young Quills award-winner

“Gritty without being gruesome, unflinching without being lurid, Out of the Smoke is a good read for anyone wanting to experience the harsh realities of life in Victorian London. Following Billy as he struggles to climb his way up from the bottom rung of the ladder, it is a story rich in menace and hope, not to mention a great deal of atmosphere and detail, much of which will be new to seasoned readers of historical fiction.“

Keith Dickinson, author of ‘Dexter and Sinister’ and ‘The Dragonfly Delivery Company’

Buy the book

A thrilling Victorian adventure

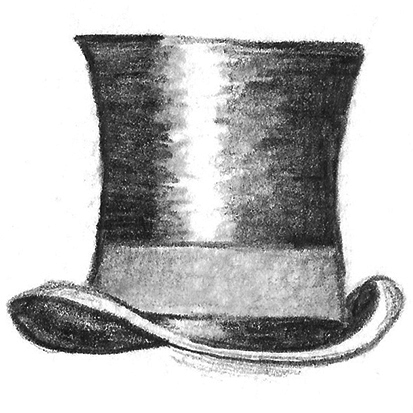

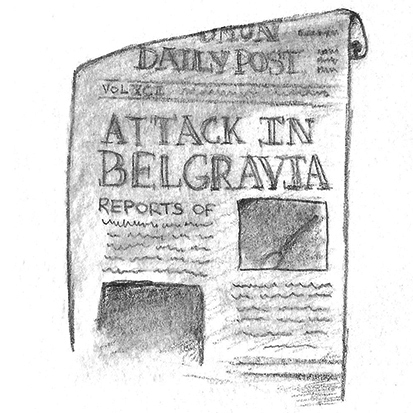

Victorian London is a lawless city. Street gangs engage in running battles in broad daylight, while pickpockets, burglars and sneak-thieves plague even the wealthiest boroughs. The Metropolitan Police, still in its infancy, struggles to hold back the rising tide of violence and petty crime.

Children are the worst affected. Homeless, orphaned, uneducated, and frequently starving, they must choose between backbreaking work—twelve-hour shifts on the factory floor, or else squeezing up narrow chimneys—or a fight for survival on the streets. Either way, life is short and brutal, and few see adulthood.

Most people in positions of power would prefer not to acknowledge their existence, much less reach out to help them. But one man is determined to do all he can to lift up the downcast and shed light into the darkness: a man known as the Poor Man’s Earl …

Set on the streets of Victorian London, ‘Out of the Smoke’ is a gripping tale of faith and survival. Pursued by notorious gang boss Archie Miller, Billy the chimney sweep is forced to go on the run and fight for his life in the criminal underworld. No matter how hard he tries to escape he just ends up being drawn deeper and deeper into crime, and closer and closer to Archie Miller.

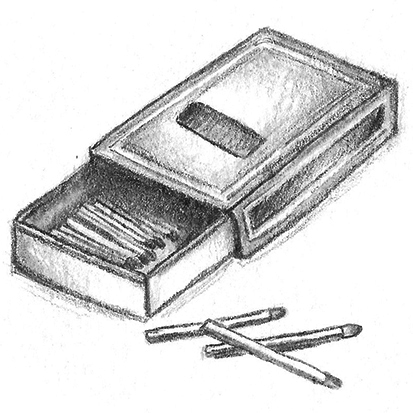

From night-time raids to pitched street battles, burglarly and arson, this book takes the reader on a breakneck journey and highlights the importance of the work of noted Christian social reformer Lord Shaftesbury.

The book explores questions of identity and friendship, loyalty and faith. When it comes right down to it, who can Billy trust? Who are his friends? Who can he depend upon if it isn’t himself?

A book that will resonate with young people today, surrounded by hard choices and the ever-present shadow of modern street gangs.

Illustrations

All images copyright Jaime Dill 2021

Extract

Chapter 1

Up, Up, Up

“Get in there!”

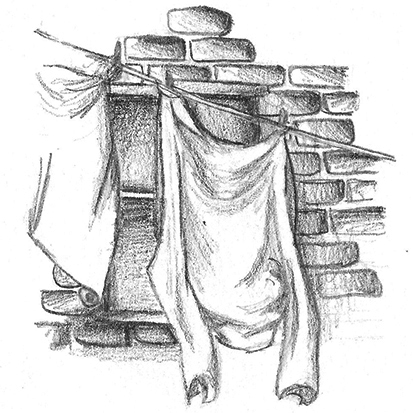

Gerard tightened the rope around Billy’s ankle with a sharp tug and shoved him towards the sheet-draped fireplace. Billy stumbled and almost fell, but he bit back the retort that came all too easily to his lips. It wasn’t worth arguing with Gerard: he would only get fresh bruises for his trouble. Gerard was the master sweep, and Billy was just an apprentice; apprentices kept their mouths shut and did as they were told, or they regretted it.

He ducked behind the sheet. It was dirty, and it stank, but at least it shielded him from Gerard. He crouched, bending almost double as he stepped over the grate and into the remains of the last fire. Mercifully the ashes were old, warm on his bare feet rather than burning hot—but he would have barely felt them anyway. Years of burns and scrapes had turned his soles into a mass of calloused skin, along with his palms, his knees, and his elbows.

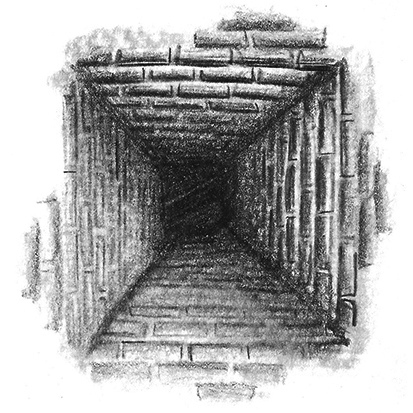

From his crouched position he peered up into the chimney, a black hole in the dim light. There were only two ways he could go now: up into that cramped hole, or out to face another beating.

Unless he got stuck. Then it would be neither, and he would stay where he was until they got him out, dead or alive.

Billy had seen it happen before. The lad had been just eight years old, and a sweep for only a couple of weeks—sold to Gerard by his father for a few guineas. Billy had never even asked his name. The boy had cried when Gerard made him go up his first chimney, and had carried on crying when he wedged himself fast. It was only when the crying stopped that Billy knew he would not be coming down again.

He had watched as the mason took apart an upstairs wall brick by brick, until finally the body tumbled on to the floor in a cloud of soot and ash. Billy had watched them wrap it in a sheet and carry it down the backstairs and into the street. After that? A quick burial in one of the common graves, most likely. That was what happened to sweeps. They were cheap, replaceable, and soon forgotten.

Not to Billy, though. Hardly a day went by when he didn’t think about that lad—not out of pity or remorse, but as a warning, a reminder of what happened if you were not careful up there.

He reached up with both hands, feeling for the smoke shelf, a cramped ledge above the hearth that drew the air through the fireplace and up the narrow flue that formed the spine of the house.

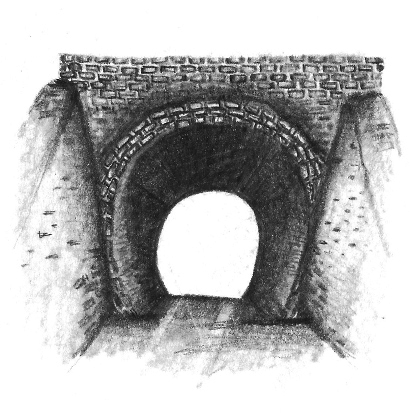

Above the smoke shelf, the brickwork sloped up sharply towards a square black hole, barely ten inches wide, which was the opening of the flue. Once inside he would have to worm his way through unknown dirt and grime, twisting and turning around any number of tight corners to reach the top.

Billy grasped his stubby sweep’s brush in one hand, and with the other jammed his cap down over his face. There would be no need to see, up there in the flue. It was black as pitch anyway, and no way to go but up.

He took a deep breath, raised his arms, and slowly wriggled himself into the hole.

Gerard was the closest thing to a father Billy had ever known—if a father was a drunk with squinting eyes, yellow teeth, and a wiry black beard as thick as the brushes that were his livelihood. Billy had been sold to Gerard when he was five years old; ‘indentured’ they called it, all legal, with papers signed before a magistrate. He supposed his parents had been either too poor or too overwhelmed with children to keep him, but either way the result was the same: from that moment he had belonged to Gerard, and he was a climbing-boy whether he wanted it or not.

He did not remember anything much of his life before then, nor of his first few months with Gerard. He had a fleeting memory of a tiny room up a narrow flight of stairs, and of being constantly cold; but after that the next thing he could remember was the first time he got stuck, and the pure unmingled terror of realising he had brought his knees up too far, jamming himself in the shaft. It had not been a bad jam—he had freed himself in a minute or so—but he had never forgotten the blind overwhelming panic, the feeling that the flue was squeezing him like a vice. It had taught him that life in his new world was fragile, and that a chimney would swallow him alive if he gave it half a chance.

Six years he had been with Gerard now, and hundreds, if not thousands, of chimneys climbed and swept. The fear no longer gripped him—he saw each flue as a challenge, an adversary to be wrestled and beaten—but he never forgot the spectre of death hovering nearby, ready to pounce.

Sometimes he dreamed that he was climbing a flue, and that just above him was Death himself, a grinning skeleton holding a scythe and an hourglass. Death would not say anything, would not touch him or hurt him, and Billy was never afraid. All the old skeleton would do was check the hourglass now and again, patiently watching the grains of sand trickle away.

As it turned out, he was a rare prize for Gerard: one of those boys who reaches a certain height then grows no further. Even at eleven he was no taller than boys three years younger than him, and his sparse diet kept him lean. His wiry frame and short stature meant he was able to squirm through the narrowest of flues and around the tightest of bends, and his age and experience had made him tough and unafraid: he was the perfect climbing-boy.

As one of the older boys he got to eat on most days—a crust of bread here, a slop of stew there, beer to drink and, if he was really lucky, the odd swig of gin— but even so the pangs of hunger were constant and unyielding.

He knew what it was like to be one of the little ’uns—lads of five or six, red-eyed, gaunt, noses streaming, trembling like leaves, watching him greedily as he gnawed on his scraps. He felt sometimes that they would eat him if they could. He knew that was what they were thinking, because the same thought had come to him when he was their age, when other boys had been the ones crouching in the corner with an end of mouldy bread. If a scrap happened to slip through his fingers they were on it like rats, fists flying, elbows gouging, teeth biting in a desperate frenzy.

He didn’t blame them. If they didn’t fight, they wouldn’t eat. All they were doing was surviving.

Billy climbed, jamming his back against one wall with his forearms and knees against the other, inching slowly, caterpillar-like, dislodging the filth that had accumulated from months or even years of fires burning in the hearth below.

Up, up, up: scrubbing, scraping, hacking at the soot and smut, shaking off the dirt and grime that showered down all around him. Up, up, up: inch by inch, scraping his back on the burned brick, ignoring the pain.

He stopped, panting, and rested with his feet against one side of the shaft and his knees against the other. It was a risky position—boys got jammed doing it—but it gave him a chance to catch his breath, and to ease the burning pain in his arms and shoulders. He could not stay for long, but even a few seconds was respite enough.

There were few moments in the day that he really had to himself. Back at the House (their name for the bare loft Gerard called home) all the boys slept and ate together, piled one across another on the soot-stained sheets they tied across the fireplaces and draped over clients’ furniture. Out on the streets they went in pairs, older and younger, calling out, “Sweep! Sweep!” in the cold dark before dawn, with Gerard not far behind to make sure none of them bolted.

But up in the flue Billy was truly alone, hidden from prying eyes, just him and the darkness. Here he could have a few seconds to himself, and those few seconds were worth more than gold.

A yank on the rope around his ankle nearly dislodged him, and he pressed himself hard against the brickwork as his heart hammered. That was Gerard. Even a few seconds’ pause was too long. If he waited much longer there was the risk that Gerard would set a fire in the hearth to drive him up, like he did with some of the little ’uns.

“All right! I’m going!” Billy yelled back down the shaft, then braced his shoulders, raised the brush, and started up the flue again.

Up, up, up: clearing, scrubbing, chipping, coughing. Up, up, up: burrowing, squirming, panting and sweating until, at long last, he felt a coldness on his up-stretched hands and a few seconds later they emerged from the top of the flue into the fresh air.

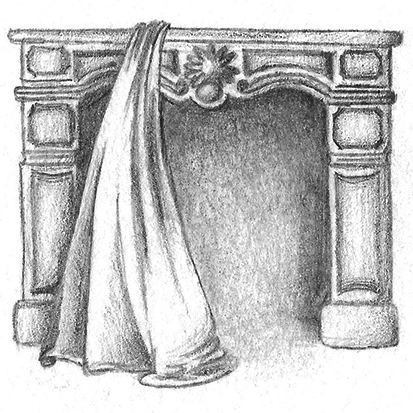

Billy wriggled himself the rest of the way and pulled himself up and out of the chimney pot so that he hung by his armpits. There he rested for a moment, looking out over the darkened city.

The black night sky above him was slowly turning to muddy blue-grey as a new day dawned. A sea of rooftops spread out all around him, rising and falling, the scattered chimney pots like bobbing buoys; already thin streams of grey smoke had begun to rise skywards from them, as the morning fires were lit in kitchens and bedrooms across the city. His eyes followed the crowded mass of buildings down towards the river, where the great dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral rose serenely over the sleeping metropolis, and for a few seconds he felt oddly at peace.

He closed his eyes and breathed in the freezing air, catching the familiar smells: the acrid bitterness of chimney smoke, the sharp undercurrent of sewage, the barest hint of a briny breeze from the nearby Thames. At times like this he could almost forget the hell that awaited him below.

A shout echoed over the rooftops. Billy turned to see another blackened face poking out of a chimney pot a few houses along the street. It was Tosher, one of the other boys in Gerard’s gang, and the only person Billy would have called a friend.

“Hey! Billy!” Tosher shouted, grinning and waving. He was a year older than Billy, and a few inches taller, but far skinnier. Above his soot-stained features, a shock of bright red hair stuck out at all angles. Tosher’s hair was a running joke in the gang: so thick, the little ’uns said, that Tosher didn’t need a brush to clean a flue, as long as he took off his cap before he started up it. Tosher didn’t mind being the butt of the joke—he just laughed along with them and shook his hair so that a cloud of soot and ash rose all around him.

Tosher had been with Gerard the longest out of all of them, so now Gerard trusted him enough to lead his own gang of sweeps. All the boys wanted to go with Tosher: he actually enjoyed the climbing, and would not let them go up unless the flue was too small for him to fit. He also hardly ever beat them, unless he really had to.

“How was yours?” Tosher called.

Billy shrugged. “Fine,” he said. “Yours?”

“Tight.” Tosher grinned, as if this was a good thing. “Nearly got meself jammed. Had to squirm like a beast to get out!”

He cackled, but though Billy smiled he could not laugh with him. There was something about Tosher that was not quite right—he savoured the risk that came with being a climbing-boy, loved the suffocating darkness, the tight spaces, the constant struggle against danger and death. Billy did not savour these things: every time he went up the flue he reminded himself that he was never more than a moment or two away from a grisly fate.

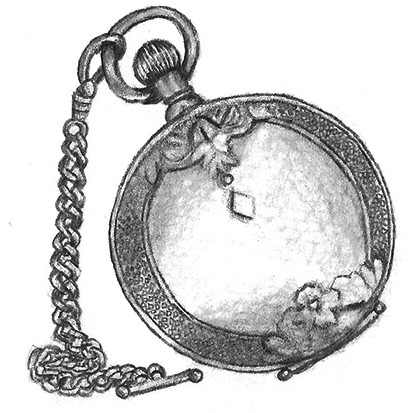

“Here!” Tosher called, putting a hand down the chimney pot and rummaging around. “Look what I got!”

He drew something out and held it aloft. It was too far away to see, but it glinted in the dawn. Billy squinted, trying to get a better view.

“What is it?” he shouted.

But Tosher had already slipped whatever it was back inside the chimney pot. He gave an exaggerated wink, tapping on the side of his too-large nose. “All in good time, Bill! All in good time!”

Billy sighed. Typical Tosher. He was never happier than when he knew something Billy didn’t. “I’d better get back,” he called, pointing downwards. “Gerard’s been on my back today. Says I’ve been slow.”

As if in response, the rope around his ankle jerked, almost dislodging him from his perch. He grabbed hold of the chimney pot and peered down the flue.

“I’m coming!” he yelled, as loudly as he could, then gave Tosher one last wave. “See you at the bottom!”

He paused to take one last longing look at the spreading light of dawn as it spilled over London, then lowered himself back into the darkness for the long descent.